Firing up your car with lipids

Sometimes, when a science experiment doesn't work out, unexpected opportunities open up.

That's what Yang Yang and the Benning lab have found in their latest work on sustainable biofuels.

When they tried to transfer a method that increases energy content in a lab plant to another plant that is targeted to make biofuels, the technique did not lead to the expected result.

But in looking into why, they found out a lot about subtle differences between two different types of plants. This basic research, conducted at the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center, is crucial to furthering biofuels explorations.

The study is published in The Plant Cell.

Meet lipids: small molecules found in fats, oils, and waxes. It's lipids that provide the boundaries for all living cells.

But they do much more than surround cells. For the Benning lab, one of the more attractive characteristics is that lipids store energy. That's why we grow chubby when we don't exercise, or how birds can migrate long distances without eating.

"One of the ways to create biofuel is to have specific crops make extra lipids that we can harvest as raw material for those biofuels," says Yang, who is a post-doc with the Benning lab and first author of the paper.

Here is one way to do it. Yang works with an Arabidopsis plant (basically the guinea pig of lab plants).

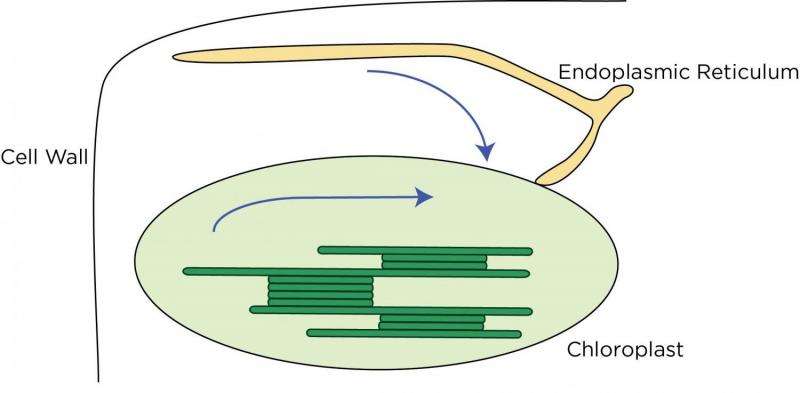

"Arabidopsis can make lipids through two sources in plant cells. Half of the precursors come from the chloroplasts (the solar power plant for the plant's survival) and half from the endoplasmic reticulum, a massive cellular factory."

She lets the leaves develop properly. Then she blocks the transfer from the endoplasmic reticulum, which causes extra lipid droplets to accumulate in the leaves and stems.

The idea would be to retrieve those lipids for industrial biofuels. "But Arabidopsis is not a suitable plant. We just use it for preliminary experiments since it is well-studied."

"We are interested in plants like switchgrass or sorghum. But when we tried applying this lipid approach to a relative of such plants, Brachypodium (nicknamed Brachy), it unexpectedly did not work. It was a surprise!"

![Brachypodium. Credit: Neil Harris, University of Alberta (Own work) [GFDL or CC BY-SA 4.0-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0], via Wikimedia Commons Firing up your car with lipids](https://scx1.b-cdn.net/csz/news/800a/2017/2-firingupyour.jpg)

Digging in, they found some very cool stuff about the biology of grasses.

The building of centaurs

It turns out that the biofuel grasses, like Brachypodium, get their lipids only from the endoplasmic reticulum.

"That is the common feature between Brachy and Arabidopsis - that movement of lipids from the endoplasmic reticulum to the chloroplast. But somehow, blocking that pathway didn't lead to extra oils in Brachy."

Yang narrowed the difference down to three proteins originally discovered in the Benning lab – TGD1, TGD2, TGD3 – found in that common transport machinery in both plants.

And in a process, a bit like building a centaur (half-man/half-horse), she systematically took pieces of the Brachy protein TGD1 and placed them, piece by piece, back into the Arabidopsis counterpart.

The idea was that once the distinct part of the Brachy protein made it into Arabidopsis, the biofuel technique would stop working Arabidopsis, as it originally did.

"We nailed the difference between the two plants to just 27 amino acids from TGD1. In the big picture, that is an extremely small difference."

Yang thinks the reason is that the three proteins, although similar in both plants, evolved differently over time. "They probably had to co-evolve in each plant. That means that, if one protein changed, the others had to adapt to preserve the overall transport function."

So why does the idea work in the one plant only?

![Oil drop. Credit: Slashme (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons Firing up your car with lipids](https://scx1.b-cdn.net/csz/news/800a/2017/4-firingupyour.jpg)

Yang thinks that, since Arabidopsis has two ways to make lipids, blocking one might encourage the other to pick up the slack. Somehow, we end up with extra useful lipids in the leaves.

Brachy has the one way only, so it doesn't have any backup plan when that is blocked.

"One takeaway is that, although plant biologists have studied Arabidopsis extensively over decades, our knowledge doesn't necessarily transfer elsewhere. Still, we have discovered some great biology about how plants work in subtle different ways."

Yang and Benning are back to the drawing board. They are now looking at different strategies to get lipids made inside the plant stem.

The search continues.

More information: Yang Yang et al. Co-evolution of Domain Interactions in the Chloroplast TGD1, 2, 3 Lipid Transfer Complex Specific to Brassicaceae and Poaceae Plants, The Plant Cell (2017). DOI: 10.1105/tpc.17.00182

Journal information: Plant Cell

Provided by Michigan State University