Leviathan polymer brush made with E. coli holds bacteria at bay

A lab goof with an enzyme taken from bacteria has led to the creation of the Leviathan of polymer brushes, emerging biocompatible materials with the potential to repel infectious bacteria.

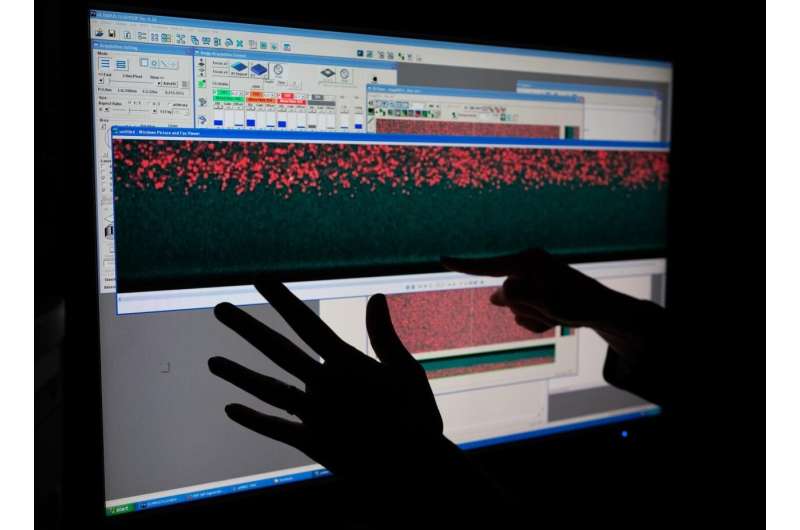

Polymer brushes are surfaces normally covered with nanoscale bristles made of polymers, spaghetti-like molecular chains that are synthesized chemically. But in a new study, a team led by researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology stumbled onto a biological technique to improve on the brushes by growing the bristles into giants 100 times the usual length.

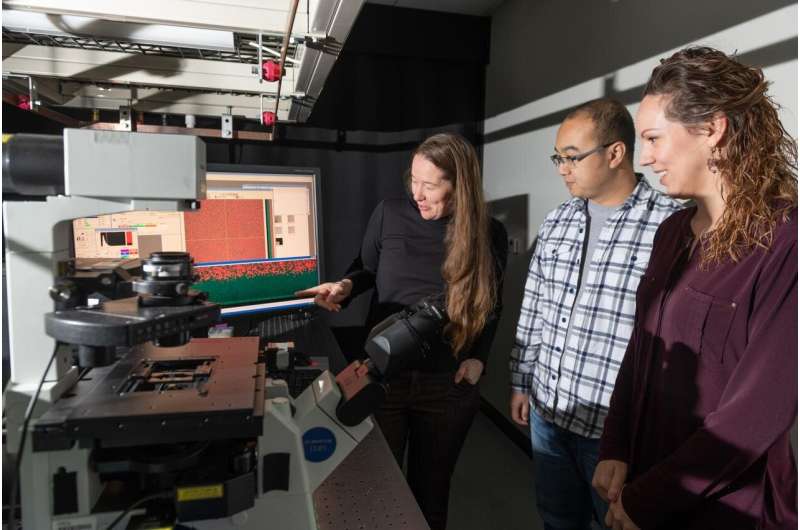

"We were putting the enzyme onto a surface to observe it for a totally different experiment, but we put too much on the surface too densely, and—boom—we ended up with the thickest, longest polymer brush we'd ever seen or heard of," said Jennifer Curtis, who led the study and is an associate professor in Georgia Tech's School of Physics. "They were so big you could actually see them under an optical microscope instead of having to feel them with an atomic force microscope or use other methods needed for more customary polymer brushes."

The researchers diverted attention from the original study to pursue the freakishly large new brush.

To bacteria encroaching on them, the brush's bristles are a virtually impenetrable, squishy thicket that keeps microbes out in lab observations. It hinders the spread of biofilms, bacterial colonies that join together to form a tough material that makes killing the bacteria difficult.

Biofilm bulwark

"The human immune system has a hard time with biofilms. Antibiotics don't work very well on them either. In water filtration, biofilms can stick tenaciously, too. If you have a hyaluronan brush on a surface, a biofilm can't stick to it," Curtis said.

Hyaluronan, the compound in the bristles, is a polysaccharide, a chain of sugar molecules, and is naturally widespread in and around our cells. It is also known to many from its use in cosmetic moisturizers.

The enzyme that makes the hyaluronan bristles on the brush is hyaluronan synthase, and it circumvents more tedious chemical synthesis by effortlessly extruding extremely long bristles. The enzymes also can replace bristles when they break off, something chemically synthesized brushes cannot do, which limits those brushes' durability. Still, use of the synthase is unorthodox.

"Brush people say, 'What are these enzymes doing here?' because they're looking for chemistry, and biologists wonder what the brush has to do with biology," Curtis said.

The team published the new study, Self-regenerating giant hyaluronan polymer brushes, in the journal Nature Communications in December 2019. The research was funded by the National Science Foundation.

Engineered E. coli

The researchers engineered bacteria to overabundantly produce the enzyme by inserting hyaluronan synthase genes from the bacteria Streptococcus equisimilis into E. coli then they harvested the enzyme.

"We shattered the bacteria into a bunch of non-living gooey fragments then adhered their membrane to surfaces, and the synthase extruded the brushes," Curtis said.

The enzymes can be switched on and off, and adjusting salt concentration or pH in the solution around the brushes makes the bristles extend to a straight form or curl up into a retracted form. Functional additives like antibacterials could be embedded in brushes.

Something like a catheter could conceivably one day be coated with brushes to remain bacteria-free, and the thickness of the wiggly brushes would also act as a lubricant by preventing frictive contact with the surface beneath them. Some human cells key to the healing process are actually able to sink through the bristles, which could have potential for medicine.

"For a chronic wound that won't heal, you may be able to design a bandage that encourages new cell growth but keeps bacteria out," Curtis said.

Biophysics research

The researchers' fortuitous detour into the giant brush has expanded possibilities for their original intent of studying enzymatic hyaluronan in isolation.

"We constantly deal with the coupling of biochemistry, chemical signaling, and mechanics, so having something that isolates the mechanics from the signaling so we can focus on just the mechanics is really useful," Curtis said.

More information: Wenbin Wei et al, Self-regenerating giant hyaluronan polymer brushes, Nature Communications (2019). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-019-13440-7

Journal information: Nature Communications

Provided by Georgia Institute of Technology